The young boy wanted a better view of the silverback gorilla living at the Cincinnati Zoo.

On Saturday morning, the zoo housed 11 western lowland gorillas. By Saturday evening, the population of the zoo’s Gorilla World had been reduced to 10.

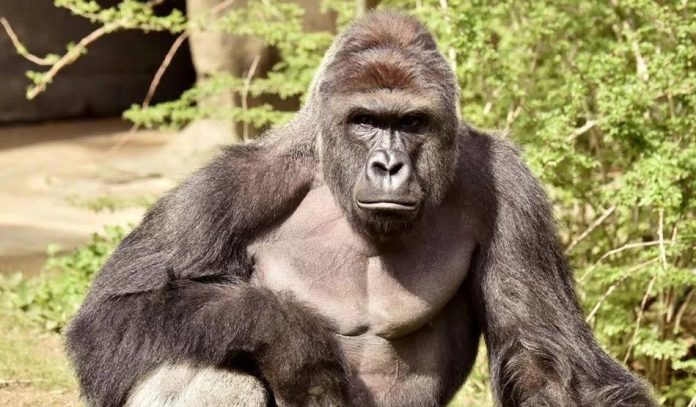

As he struggled to find a good vantage point, the boy, whose name has not been released, tumbled into a moat surrounding the enclosure. A 17-year-old, 400-pound silverback ape named Harambe grabbed the child, dragging him through the concrete moat. To save the boy from further harm, a staff member fatally shot the ape.

“The gorilla could have killed him if he wanted to,” noted Derek Spielman, a wildlife pathologist and conservation biologist at the University of Sydney, told The Washington Post in a phone interview.

The child survived his encounter with the great ape.

In the aftermath of the event, The Washington Post reported, critics of Harambe’s shooting called for “justice” on social media. (Spielman added that, had this happened in Australia, he believes zoo officials would have attempted to tranquilize the ape first, only turning to lethal weaponry if the darts were ineffective.)

The Cincinnati Zoo defended its actions. “The Zoo security team’s quick response saved the child’s life,” said the director, Thane Maynard, in a statement on Saturday. “We are all devastated that this tragic accident resulted in the death of a critically-endangered gorilla.”

Much of the wrath of social media focused on the mother of the child for letting the 4-year-old get away. But the handling of animals in captivity came under fire as well, along with the idea of them being in captivity at all.

Harambe’s death comes at a time when zoos and circuses are overturning long-standing traditions, in part due to increased scrutiny following “Blackfish,” the 2013 documentary on the killer whale that fatally attacked trainers at SeaWorld. In what commentators have attributed to the so-called “Blackfish” effect, SeaWorld’s stock price plunged, its attendance decreased and the aquarium terminated its breeding program. In early May, elephants performed at a Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey Circus for the last time, ending a legacy of live pachyderm entertainment that had lasted for 145 years.

Some advocates see events like “Blackfish” as signs that zoos need to rethink captivity. In March 2014, the Scientific American editorial board called for an end to captive elephant and orca whale breeding, citing the animals’ immense sizes, need for large swathes of habitat and their intelligence.

“We have to change direction, hit the brakes,” Ed Stewart, a founder of the Performing Animals Welfare Society, told the Christian Science Monitor. “We need to change the way we’re doing things.”

In the aftermath of Harambe’s death, the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals opined that gorillas have “complex needs,” which zoos “cannot even begin to meet.”

“Yet again,” PETA primatologist Julia Gallucci said in a statement on Sunday,”captivity has taken an animal’s life.”

How well gorillas fare in zoological captivity is not, perhaps, so clear cut as the issue of elephants or orcas. There have been have been accidents involving captive gorillas prior to Harambe: In 2005, a Lincoln Park zoo intern was bitten by a gorilla; in 2015, a gorilla rushed the viewing window at an Omaha zoo, finding viral fame in the fractured glass; a month later, a female gorilla died at the Melbourne Zoo after another gorilla attacked her.

But no gorilla has achieved the notoriety of Tilikum, the orca at the center of “Blackfish” who was involved with the deaths of three trainers. In fact, a captive gorilla named Jambo once protectively stood watch over a boy who had fallen into the ape exhibit at the Jersey Zoo, as the University of Salford’s Robert John Young, an animal behavior expert who studies captivity, pointed out to The Washington Post in an interview.

“Gorillas are very different from killer whales,” Young told The Post. Recreating a sufficient habitat for orcas — which can cross 60 miles in a day — would be exorbitantly expensive, he said. Gorillas, on the other hand, are in a “much more manageable situation.” Young cites the Philadelphia Zoo, which now allows its gorillas to roam through a 200-foot-long series of walkways and enclosures, as a leader in providing apes with mentally stimulating conditions. “The concept of zoos is changing quite readily.”

Still, captivity does not treat all gorillas equally. Captive gorillas frequently suffer from cardiac disease, with the Smithsonian Zoo reporting in 2011 that 30 apes take heart medication. They can be emotionally distressed as well. Laurel Braitman’s book “Animal Madness” recounts the story of Tom, a gorilla sent to a new zoo because he was a genetic match with its inhabitants. There, he shed a third of his body mass after his new ape companions began to assail him. Upon encountering his old human caretakers, according to Braitman, the gorilla began to cry.

Supporters of keeping gorillas captive note that many belong to species survival programs, in which animals are bred in captivity in the hopes of reintroduction in the wild. Two dozen scimitar-horned oryx were released in Chad in May, for instance, after years of breeding in zoos. Harambe was part of the Gorilla Species Survival Plan (SSP), which was formed in 1988 to preserve a healthy genetic stock of gorillas.

“This is a huge loss for the Zoo family,” Cincinnati Zoo’s Maynard said, “and the gorilla population worldwide.”

For gorillas, the situation in the wild can be dire. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature considers the 175,000 or so western lowland gorillas to be critically endangered, facing habitat loss, hunting and the spread of the Ebola virus.