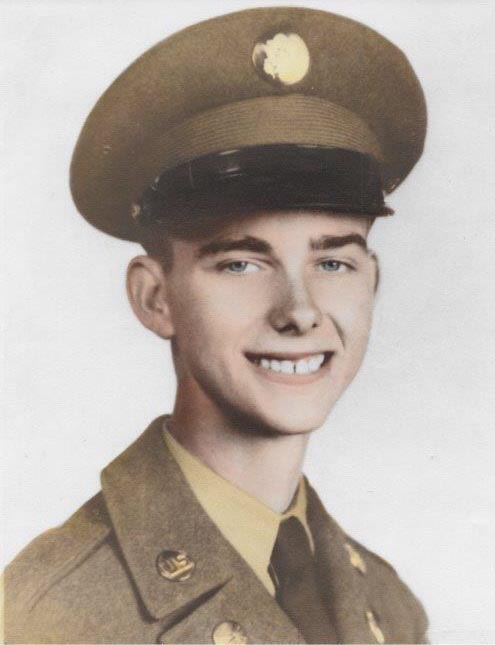

Wayne Minard knew at an early age that he wanted to be a soldier.

He joined the Army when he was 17 after persuading his mother to sign his enlistment papers. His family thought he would go on to build a lifelong career in the military.

But his career as a corporal in North Korea lasted only two years.

Minard was reported missing in action on Nov. 26, 1950, the day after Chinese communist troops attacked United Nations forces and allies near the Ch’ongch’on River in North Korea, according to the Pentagon.

Minard’s unit was later ordered to withdraw. The farm boy from rural Kansas, then 19, was never seen or heard from again.

He was taken to a prison camp and starved, Bruce Stubbs, Minard’s great-nephew, told The Washington Post.

On Feb. 16, 1951, Army Cpl. Wayne Minard died, according to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

Now, after 65 years, Minard is finally coming home. His remains will arrive in Wichita on Wednesday.

Minard’s loved ones had always thought he would never be found, his great-nephew said.

But the family saw a sliver of hope in spring 2005, when an Army recovery team learned of a North Korea burial site that contained the remains of an American soldier. Scientists had obtained DNA samples from two of Minard’s sisters, according to the Pentagon. It would take another 11 years for his remains to be positively identified.

The Pentagon released a statement in September saying that Minard was finally accounted for.

DNA tests also showed that 32 other people, including two soldiers from Minard’s unit, had been buried in that site, Stubbs said.

Minard’s death haunted his family for decades.

His mother, Bertha, never stopped blaming herself for signing her son’s enlistment papers. She died nine months after her son did.

“They say she died of a broken heart,” Stubbs said.

According to the Pentagon, Minard “was a member of Company C, 1st Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, fighting units of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Forces (CPVF)” when “enemy forces launched a large-scale attack with heavy artillery and mortar fire” on Nov. 25, 1950.

He reported missing in action the following day.

But his name “did not appear on any POW list provided by the CPVF or the North Korean People’s Army,” according to the Pentagon. “However two repatriated American prisoners of war reported that Minard died at Hofong Camp, part of Pukchin-Tarigol Camp Cluster, on Feb. 16, 1951.”

A military review board “amended Minard’s status to deceased in 1951,” the Pentagon said.

Stubbs, who was born 14 years after Minard died, knows about his great-uncle only through stories he heard from family members.

Even in war, his great-uncle kept his sense of humor, Stubbs said. After he was shot in the hand during a firefight, Minard wrote to his family and joked that the enemies weren’t very good shots.

The Army was going to bring Minard home after he was injured, but he opted to stay with his unit in North Korea.

Minard had a twin brother, Dwayne; the two were the youngest of nine children. They were “good, fun-loving farm kids” who loved playing practical jokes on their father, Stubbs said. They used to set up a bucket of water above the garage door, so the water would fall on their father’s head every time he drove the tractor back into the garage.

Minard will be buried with full military honors on Saturday in the unincorporated community of Furley, Kan., where he grew up.

To this day, 7,784 Americans remain unaccounted for from the Korean War, according to the Pentagon.

A sister who lived in California was the only immediate family member who lived long enough to hear about her brother’s remains being identified in September. She had long been ill, but when she heard the news, “she opened her eyes for the first time in a long time, and smiled,” Stubbs said.

She died shortly after.

“It’s bittersweet. We’re all very, very happy that he is finally coming home,” Stubbs said. “I wish my grandma and his sisters would’ve been around to see him come home. They never stopped thinking about him. They never stopped agonizing over him.”

Featured Image: Bruce Stubbs.

(c) 2016, The Washington Post · Kristine Guerra