The inspector general for the Environmental Protection Agency said Thursday that the agency should have issued an emergency order to protect residents of Flint, Michigan, from lead-tainted water seven months before it actually did.

The agency watchdog found that the EPA had “the authority and sufficient information” to force state officials to fix the city’s escalating water problems in June 2015. But the EPA did not issue its emergency order until Jan. 21, long after it became clear that those state officials’ failure to properly treat the water had left the entire city – including thousands of young children – exposed to elevated levels of lead.

“These situations should generate a greater sense of urgency,” Inspector General Arthur A. Elkins said in a statement Thursday. “Federal law provides the EPA with the emergency authority to intervene when the safety of drinking water is compromised. Employees must be knowledgeable, trained and ready to act when such a public health threat looms.”

Thursday’s findings come amid a broader inquiry into the federal agency’s actions in Flint. Elkins recommended the EPA update its 25-year-old internal guidance on the use of that emergency authority and require drinking-water staff to attend training on when to use it.

In a contentious hearing on Capitol Hill this year, EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy conceded that the agency was too slow to intervene in Flint’s water-contamination crisis. But she insisted that under the law, it had done all it could to protect Flint’s 95,000 residents. She refused to accept blame for the catastrophe, instead laying the responsibility on Michigan’s Republican Gov. Rick Snyder.

She said state officials “slow-walked everything they needed to do. That precluded us from doing what we had to do,” she told the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee. “We were strong-armed. We were misled. We were kept at arm’s length. We couldn’t do our jobs effectively.”

Even so, Thursday’s inspector general report notes that by April 2015, the EPA “discovered that the necessary corrosion control had not been added to the community water system” after the city switched its water source to the Flint River a year earlier. By June 2015, the EPA also knew that the water in “at least four homes” in Flint had tested for lead concentrations beyond the federal action level of 15 parts per billion. The agency also knew “that the state and local authorities were not acting quickly to protect human health,” the inspector general found.

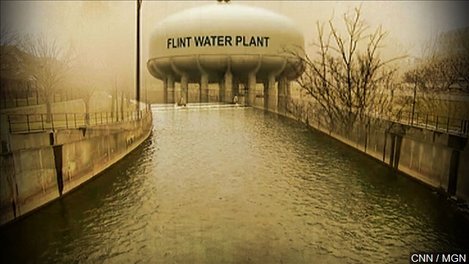

For decades, Flint had bought its water from Detroit. It was piped from Lake Huron, with anti-corrosion chemicals added along the way. But in early 2014, with the once-thriving industrial city under the control of an emergency manager appointed by Snyder, officials switched to the river water in a bid to save money. The state failed to ensure that corrosion-control additives were part of the new water supply. That allowed rust, iron and, most dangerously, lead from aging pipes to flow into residents’ homes.

Residents began complaining almost immediately that their tap water was brown and foul-smelling. They reported an array of problems, from hair loss to skin rashes appearing after baths. Repeatedly, state and local officials dismissed their complaints and assured them the water was safe. It wasn’t.

The tap water in Flint remains unsafe to drink even now, some 10 months after the EPA’s emergency order. Officials have said that showering or bathing in it no longer is a risk, but many residents remain skeptical. Tens of thousands of people there still rely on bottled water to drink, bathe and cook.

(c) 2016, The Washington Post · Brady Dennis