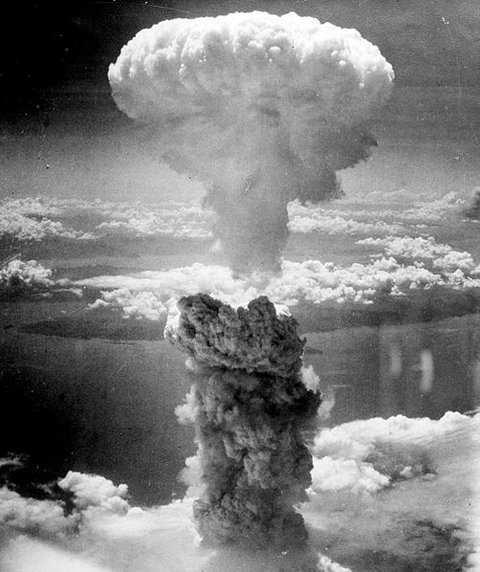

HIROSHIMA, Japan – For nearly 71 years, the consequences of the world’s first atomic bombing have remained close to the surface here.

Construction workers digging under the Peace Memorial Museum recently discovered the charred and mangled remains of a bicycle, a rice paddle, a toothbrush and a fountain pen, tangible artifacts of a civilization that was buried in ash on Aug. 6, 1945.

The memory of that moment has defined this Japanese city of 1.1 million for more than seven decades, but the ghosts of that horrifying past also have prevented a final reconciliation with the nation that dropped the bomb.

No sitting U.S. president has ever visited Hiroshima, out of concern that such a trip might be interpreted as an apology. The bombing killed 140,000 people but has been viewed by many Americans as a necessary evil to end World War II and save the lives of U.S. troops.

Today, however, there is growing sentiment inside the White House that President Barack Obama, who in his first year envisioned a world without nuclear weapons, should cap his final year with a grand symbolic gesture in service of a goal that remains well out of reach.

No final decision has been made, but aides have begun exploring the possibility of Obama spending several hours in Hiroshima in May, after attending the Group of Seven summit in Ise-Shima, halfway between Tokyo and Hiroshima. One senior Obama administration official, in an interview, suggested that the president could potentially deliver a speech there that evokes the nonproliferation themes of his address in Prague in 2009. Such a move would draw international attention in a more emotional fashion than did his nuclear security summit in Washington last week.

On Sunday, Secretary of State John F. Kerry will arrive in Hiroshima for the G-7 foreign ministers’ conference – the first-ever visit by the United States’ top diplomat – and White House advisers are closely watching his time there as a prelude to a possible Obama trip.

“I think the president would like to do it,” said John Roos, who served as the U.S. ambassador to Japan from 2009 to 2013 and in 2010 became the first American diplomat to participate in the annual Aug. 6 memorial observance in Hiroshima. “He is a person who bends over backwards to show respect to history, and it does advance his agenda.”

The White House is well aware of the potential for domestic criticism around a Hiroshima trip, especially in an election year. Republicans have consistently portrayed Obama’s foreign policy as feckless and weak, and the president was ridiculed in 2009 when he bowed to the Japanese emperor in Tokyo. During the 2012 presidential campaign, GOP nominee Mitt Romney accused Obama of undertaking a global “apology tour.”

In Japan, anticipation is high ahead of Kerry’s arrival, and local officials said the public has long been enamored of a potential visit from Obama. Yet even here, the geopolitics are complicated, in light of China’s rise and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s pursuit of a stronger Japanese self-defense strategy.

Abe has ramped up defense spending and won new powers for Japan’s pacifist self-defense forces to play a stronger international role in the face of China’s growing military capabilities and a nuclear-armed North Korea. Last year, on the 70th anniversary of the war’s end, Abe made a concentrated effort to resolve lingering World War II-era disputes with Seoul and Beijing that had complicated relations between the Asian powers.

“On the security side, particularly in East Asia, the rise of China poses a challenge to Japan’s security, and the military buildup of China reminds us of the importance of balance,” said Nobumasa Akiyama, nuclear security policy professor at Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo. “Here in East Asia, there is a divide between the nuclear abolitionists and the security people.”

Some Abe aides fear that an Obama appearance in Hiroshima would renew debate in the United States over Japan’s imperial past and complicate the prime minister’s security agenda in Asia by forcing him to respond to U.S. campaign-trail criticism and justify his policies. One Abe adviser, in an interview, suggested that Obama delay a visit until after he leaves office; former president Jimmy Carter toured the memorial park in 1984, several years after he left the White House. And Abe himself visited Hiroshima last August for the 70th anniversary memorial ceremonies.

Japanese foreign policy analysts said Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida, who was born in Hiroshima and is more moderate than the conservative Abe, is more committed to the disarmament message and to Japan’s pacifist post-war policies.

One Tokyo-based academic who closely advises Abe said that “no matter how allergic the Japanese have been on the nuclear issue, let’s just face it: On the other side of the coin is the continued commitment from the United States to provide protection to Japan under its nuclear umbrella.”

This official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss Abe’s thinking, added that China “is the only country constantly investing in a nuclear arsenal. The number of warheads is on the rise. . . . I wonder if President Obama and his advisers are fully aware of this subtle but substantial difference between Europe and East Asia.”

Obama administration officials emphasized that Tokyo has not made any objections, publicly or privately, and suggested that Abe has many advisers with differing opinions.

White House aides say they are confident that Obama can pay respects to the victims of the war – on both sides of the Pacific – without provoking a major political backlash in the United States. The feeling within the White House is that a Hiroshima visit, while not crucial to the future of the U.S.-Japan alliance, would offer the president another opportunity to recognize history without being, in his words, “imprisoned” by it.

In his second term, Obama has made historic trips to Myanmar and Cuba and negotiated a landmark nuclear deal with Iran.

“It’s not lost on us that this would bring the Prague speech and the conception of a world without nuclear weapons full circle and offer a very poignant platform for a message that is so central to the Obama presidency,” said one senior administration official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because plans are not finalized. “This is not a triple bank shot. The risks are manageable.”

Local officials in Hiroshima said that most Japanese would be satisfied if the president were to express empathy and renew his call for disarmament. A former mayor once termed his constituents the “Obamajority” to signal their enthusiasm for the president’s nonproliferation agenda.

“If he comes to Hiroshima, I think the majority will welcome him because we see that he’s trying to move things forward,” Hidehiko Yuzaki, the governor of Hiroshima prefecture, said in a recent interview. “The difference between President Obama and the heads of other nuclear weapon countries is that, of course, the U.S. dropped the bomb. But we’re not expecting President Obama to apologize.”

In his city hall office, Hiroshima Mayor Kazumi Matsui keeps a three-ring binder full of photos of the artifacts discovered by construction workers under the peace museum. He flipped through them for a foreign visitor on a recent day, before pulling out a pre-war map of the city and explaining that 4,000 people lived on the site that is now the memorial park.

Matsui, 63, said he hoped the foreign ministers “touch the emotions, feelings and thoughts of A-bomb survivors,” who are called “hibakusha” in Japan. (His mother, uncle and paternal grandmother were among them.) On Monday, Kerry is expected to join his fellow foreign ministers to lay flowers at the cenotaph in Peace Memorial Park.

“We are not looking at the past, but we are future-oriented,” Matsui said through an interpreter. “President Obama is well known for the message he gave in Prague in 2009, saying he would like a world without nuclear weapons. He was awarded the Nobel [Peace] Prize. If he truly understands our sentiments, [a visit] would play an important role for his inner thoughts, and the role he can play as a politician.”

But the hair-trigger sensitivities have been weighed by each of the American officials who have been invited to Hiroshima. In 2008, then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-California, became the highest-ranking U.S. government official to visit the city when she participated in a global summit of the heads of parliament.

Pelosi, now the House minority leader, recalled in an interview that she discussed the optics ahead of time with two Democrats who had served as ambassadors to Japan: Walter Mondale and Thomas S. Foley. They told her that a boycott of the event by the American delegation would result in “a loss of face” for their hosts and represent a greater political risk.

“The White House will have to weigh all of that,” Pelosi said. “This is not about Japan or the U.S. even. It’s about humanity.”