TECUMSEH, Okla. — They had been expecting a full processional with a limousine and a police escort, but the limousine never came and the police officer was called away to a suspected drug overdose at the last minute.

That left 40 friends and relatives of Anna Marrie Jones stranded outside the funeral home, waiting for instruction from the mortician about what to do next. An uncle of Anna’s went to his truck and changed from khakis into overalls. A niece ducked behind the hearse to light her cigarette in the stiff Oklahoma wind.

“Just one more thing for Mom that didn’t go as planned,” said Tiffany Edwards, the youngest surviving daughter. She climbed into her truck, put on the emergency flashers and motioned for everyone else to follow behind in their own cars. They formed a makeshift processional of dented pickups and diesel exhaust, driving out of town, onto dirt roads and up to a tiny cemetery bordered by cattle grazing fields. In the back there was a fresh plot marked by a plastic sign.

“Anna Marrie Jones: Born 1961 – Died 2016.”

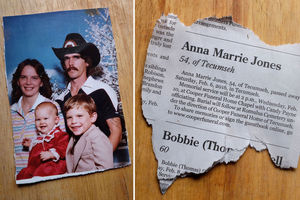

Fifty-four years old. Raised on three rural acres. High school-educated. A mother of three. Loyal employee of Kmart, Walls Bargain Center and Dollar Store. These were the facts of her life as printed in the funeral program, and now they had also become clues in an American crisis with implications far beyond the burnt grass and red dirt of central Oklahoma.

White women between 25 and 55 have been dying at accelerating rates over the past decade, a spike in mortality not seen since the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s. According to recent studies of death certificates, the trend is worse for women in the center of the United States, worse still in rural areas, and worst of all for those in the lower middle class. Drug and alcohol overdose rates for working-age white women have quadrupled. Suicides are up by as much as 50 percent.

What killed Jones was cirrhosis of the liver brought on by heavy drinking. The exact culprit was vodka, whatever brand was on sale, poured into a pint glass eight ounces at a time. But, as Anna’s family gathered at the gravesite for a final memorial, they wondered instead about the root causes, which were harder to diagnose and more difficult to solve.

“Life didn’t always break her way. She dealt with that sadness,” said Candy Payne, the funeral officiant. “She tried her best. She loved her family. But she dabbled in the drinking, and when things got tough the drinking made it harder.”

There were plots nearby marked for Jones’s friends and relatives who had died in the past decade at ages 46, 52 and 37. Jones had buried her fiance at 55. She had eulogized her best friend, dead at 50 from alcohol-induced cirrhosis.

Other parts of the adjacent land were intended for her children: Davey, 38, her oldest son and most loyal caretaker, who was making it through the day with some of his mother’s vodka; Maryann, 33, the middle daughter, who had hitched a ride to the service because she couldn’t afford a working car; and Tiffany, 31, who had two daughters of her own, a job at the discount grocery and enough accumulated stress to make her feel, “at least a decade or two older,” she said.

Candy, who in addition to being the officiant was also a close family friend, motioned for Tiffany and Maryann to bring over the container holding their mother’s cremated remains. They opened the lid and the ashes blew back into their dresses and out into the pasture.

“No more hurt. No more loneliness,” Candy said.

“No more suffering,” Tiffany said.

They shook out the last ashes and circled the grave as Candy bowed her head to pray.

“We don’t know why it came to this,” she said. “We trust You know the reasons. We trust You have the answers.”

—

All anyone else had so far was a question, one that had become the focal point of congressional hearings, health summits and presidential debates: Why?

Why, after 50 years of unabated progress in life expectancy for every conceivable group of Americans – men, women, young, old, rich, poor, high-school dropouts, college graduates, rural, urban, white, black, Hispanic or Asian – had one demographic group in the last decade experienced a significant percent increase in premature deaths? Why were so many white women reporting precipitous drops in health, mental health, comfort and mobility during their working-age prime? Why, over the last eight years alone, had more than 300,000 of those women essentially chosen to poison themselves?

“It’s a loss of hope, a loss of expectations of progress from one generation to the next,” said Angus Deaton, a Nobel Prize-winning economist who had studied the data.

“What we’re seeing is the strain of inequality on the middle class,” President Obama said.

“Erosion of the safety net,” Hillary Clinton said. “Depression caused by the state of our country,” Donald Trump said. “Isolated rural communities,” Bernie Sanders said. “Addictive pain pills and narcotics,” Marco Rubio said.

There were so many paths in the America of 2016 to what coroners termed “a premature and unnatural death,” and one version was what had happened to Jones: Another night of drinking that ended in the emergency room, her seventh trip in the last four years. A diagnosis of end-stage liver failure. A week in a nursing home. A quiet death followed by burial four days later.

And now her family had caravanned from the graveyard to a memorial potluck, hosted at a senior center in a part of the country where fewer people were becoming seniors. The early death rate had risen twice as fast in rural Oklahoma as in the rest of the United States, and the walls of the center were adorned with posters about prescription overdose and the phone number for a suicide hotline. Candy set up a buffet table and brought in her homemade biscuits. Other relatives came with macaroni salad, coleslaw and baked chicken. They lined the food on a foldout table near a collection of photos from Anna’s life. Here she was riding a horse on her 10th birthday. Here she was behind the register at the hamburger counter, 13 years old and straight-shouldered in her uniform.

“So proud. So confident,” said Kaitlyn Strayhorn, a friend, looking at the photo.

“She had to lie and say she was 16 to get that hamburger job,” said Junior Sides, her brother. “She was a hard worker. Had it going good there for a while.”

She had been born on the way to the hospital in the back seat of her father’s car, the ninth of 10 children, and the family joke was that Anna had never stopped hurtling her way into the world. At a time when life on the far edges of the middle class came with dependable opportunities, her older siblings left home for the quarry, the machine shop and the military, and Jones moved out along with them even though she was only 17. She rushed off to get married in Reno, Nev. She got a job at a Kmart snack bar in California and worked her way up to manager. She was good at making people feel comfortable, at listening without judgment and aligning herself with the customer. She clipped coupons for regulars and gave free drinks to people who couldn’t afford them. By the time she reached her mid-20s, Kmart was training her to become a regional manager. She had her own trailer in Ferndale, Calif., two children, two cars and a retirement savings account.

But the promotion never materialized and the marriage took work, and after a while her eagerness turned to restlessness. She drank more. She tried drugs. She left Kmart. She was arrested for drinking and for failing to pay her taxes. Her marriage unraveled and she moved home to Oklahoma with the kids. She helped push Maryann and Tiffany to finish high school, and then once all of her children left home she lived for a while with her mother, then her daughter, then her fiance and finally her son for the last years of her life.

Her brother Junior hadn’t seen her for the last several months, and in the most recent photos her skin had turned pale and the fatigue lines beneath her eyes had hardened into deep red marks. “Sick and tired of being sick and tired,” Junior said, and then he filled his plate and sat down at a table with her children and her friends.

“I think in some ways she was ready,” he said. “You can see how much it took out of her.”

“Sometimes the hard things in life eventually break you,” said Kaitlyn, Anna’s friend. Kaitlyn had lost one infant child to SIDS. She had lost another to miscarriage in the third trimester.

“It’s a test of how much you can take,” Junior said. He had been addicted to prescription pills and then recovered. He had been shot five times by his son and chosen to forgive him.

“But there’s a choice in how you handle it,” Candy said. “That’s what I always told her: You’re choosing this. I’m sorry, but you are.”

“Alcohol is a powerful drug,” Davey said.

“Everybody needs a little something,” Maryann said.

They finished eating and cleared their plates. Davey went outside to smoke a cigarette. Maryann found her way to an empty car and took a nap. After a while it was just Tiffany and a few others left in the senior center to clean up the dishes. “You have all this under control?” the last remaining relative asked Tiffany, already heading out the door, because with Tiffany it never seemed like a question. She always had it under control. She was the strongest sibling, the most responsible, the one who had gone to a year of college, the head of pricing at a grocery store, the dieter, the rare woman in rural Oklahoma whose well-being nobody seemed to worry about. And now she was alone at the sink, gripping hard onto the handle, closing her eyes.

“When does it get easier?” she said.