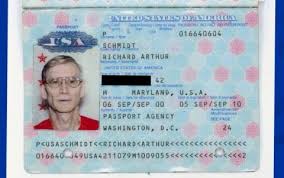

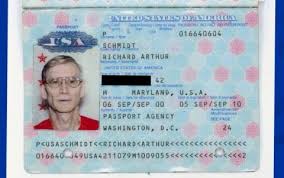

The arrest of Richard A. Schmidt, a serial child molester from Maryland, was touted more than a decade ago as a major success of a law to track and punish sexual predators globally.

Now a federal appeals court must decide whether Schmidt should be set free without any monitoring.

Schmidt, who had been an elementary school teacher, was arrested several times in the 1980s for molesting young boys in Maryland and served more than a dozen years in prison. After his release in 2002, he was accused of violating parole and fled to the Philippines and later to Cambodia, according to court records.

Shortly after Schmidt arrived in Southeast Asia, Congress passed a law giving prosecutors more power to pursue U.S. citizens suspected of sexually exploiting children in foreign countries, including those involved in sex tourism.

Schmidt was arrested again in Southeast Asia for abusing young boys and deported to the United States in 2004. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 15 years in federal prison.

Nearly a decade later, Schmidt, now 74, appealed his conviction, and last year a federal judge in Baltimore said that while the “record establishes that Schmidt is a sexual predator,” he also agreed with Schmidt’s argument: Schmidt did not break U.S. law because the crimes he pleaded guilty to did not happen in the first country he visited after leaving U.S. soil but in the second.

For prosecutors to have authority on foreign soil, U.S. District Judge J. Frederick Motz said, there must be a direct connection between the United States and the foreign country.

Motz’s opinion set up the hearing this week at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit after prosecutors challenged the Baltimore ruling.

The appeals argument does not center on whether Schmidt exploited young boys but on whether his 2005 conviction hinged on the wrong segment of his trip and whether Schmidt was still “traveling” when he left the Philippines for Cambodia.

Schmidt’s attorney, Mary E. Davis, said in court filings that Schmidt is not guilty because the travel to Cambodia was from the Philippines, where he lived, not from the United States. Schmidt had made the Philippines his home, she said, renting a house, getting a local driver’s license and working full-time.

“He was not some itinerant vagabond,” Davis said. “Schmidt left the United States with the intent not to return.”

Prosecutors said the exact timing of Schmidt’s travels is not what matters.

“Congress intended to criminalize all illicit sexual conduct by U.S. citizens abroad, regardless of when they traveled,” said Sujit Raman, chief of appeals for the U.S. attorney’s office in Maryland.

Since 2003, at least 90 Americans have been prosecuted under the law, according to the Justice Department.

Even before the Baltimore ruling, Schmidt was scheduled to be released Jan. 20, according to federal Bureau of Prisons records.

If the ruling by the Baltimore judge stands on appeal, prosecutors are concerned that Schmidt would not be supervised or registered as sex offender after his release. He would have no obligation to register under federal law or for the Maryland convictions from the 1980s.

The office of Rod J. Rosenstein, U.S. attorney for Maryland, is asking the appeals court to reinstate Schmidt’s sentence and initial terms of his plea agreement to ensure that he registers as a federal sex offender and is subject to a bar on applying for a new passport and having unsupervised contact with children.

Authorities are working on a separate track to keep Schmidt in custody, a legal process that is also tied up on appeal at the 4th Circuit.

In anticipation of Schmidt’s scheduled release, the Bureau of Prisons evaluated Schmidt and determined that he is a “sexually dangerous person.” The finding allowed the government to ask to have Schmidt civilly committed after his release from a North Carolina prison, scheduled for January.

But that separate attempt to try to keep Schmidt in custody triggered its own legal wrangling.

The prison’s finding that Schmidt was a danger came after the Baltimore judge had said he was being unlawfully held in the overseas travel incident, raising the question of whether the psychiatric evaluation done in prison is valid.

It is unclear when the Richmond, Virginia-based appeals court will rule on the psychiatric commitment case, which was argued in October.

When a warrant was issued for Schmidt’s arrest in 2002, he left for the Philippines, where he worked as a computer consultant and instructor at a local school. The next year, he was arrested for alleged sex crimes against numerous local children ranging in age from 9 to 16, according to court records.

He was released in the Philippines and fled to Cambodia in December 2003, where, U.S. prosecutors said, he spent time in guesthouses and other “temporary quarters that cater to [sex] tourists.”

In court filings, prosecutors said Schmidt never settled permanently in the Philippines and was still in transit when he fled to Cambodia. He maintained a U.S. bank account and relied on a series of tourist visas, federal prosecutors said.

Schmidt was arrested in Cambodia after child-welfare organizations notified local police about his liaisons with more young boys. He enticed them to his apartment with video games, food and English lessons, according to an affidavit filed by a U.S. immigration agent.

He was arrested at a guesthouse, where a 13-year-old boy told a U.S. immigration agent that Schmidt sexually assaulted him, according to the affidavit. Schmidt was detained and deported to face charges in the United States.

The year after Congress made it easier for prosecutors to go after sex tourists, federal officials held out Schmidt as a prime example of the type of person the law was designed to catch. He was featured in a front page New York Times article about expanded law enforcement efforts to combat child exploitation overseas.

In 2013, Congress amended the law again. It now spells out specifically that the law covers Americans residing temporarily – not just traveling – abroad.

(c) 2016, The Washington Post · Ann E. Marimow